Bone Stress Injuries and Recovery

Bone Stress Injuries and Recovery https://www.cliftonhillphysiotherapy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/IMG_2263-1024x768.jpg 1024 768 Sallie Cowan Sallie Cowan https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/7f5ef92e4282b4538250cbe3e76fe2e1?s=96&d=mm&r=g- Sallie Cowan

- no comments

Bone stress injuries are common in athletic populations and in those who have started a new weight-bearing activity. They can be a significant burden to individuals and athletes due to their long recovery times and their impact on normal daily activities while recovering. To better understand bone stress injuries, firstly we need to understand how bone reacts to new and sustained repetitive mechanical workloads.

The way in which bone stays healthy is not overtly different to other tissues in the body. For example, many are aware that our skin cells are consistently turning over; older skin is shed and new skin is created to replace it. This process happens relatively quickly for us. When we get a small cut on our arm, generally within a week or two it is well healed, because new skin cells have been generated to replace the older skin.

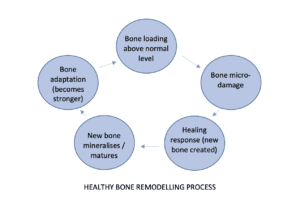

For bone cells, the process is similar, and is referred to as ‘Bone Remodelling’.

When bones are exposed to an increase in demand, or an increased ‘mechanic load’, at a cellular level the bone experiences micro-trauma/micro-damage. This sounds bad, but in fact, it is a really normal bony activity and triggers a healing response. In the vast majority of cases, this micro-trauma heals into new more resilient and stronger bone and involves no painful symptoms.

One key difference to skin cells is that this bony process takes much longer. New bone cell units require at least 3 months to fully mineralise and become mature cells (Frost, 1991)

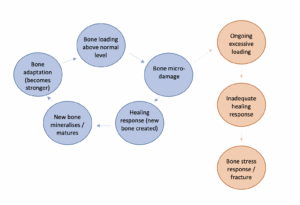

In the context of bone stress injuries, there is a discontinuity of this process, where the healing response and new bone formation process are exceeded by an imbalanced rate of micro-damage. This leads to more significant damage to the bone structure and can lead to pain and disability;

Bone stress fracture and bone stress response/reaction are terms used by health professionals. While often used interchangeably, they refer to different stages in the above process. Normal micro-damage related to loading, can progress to a ‘stress reaction’, before further progressing to a ‘stress fracture’ where we can see a distinct fracture line in the bone on certain imaging studies. In layman’s terms, a stress fracture is a more significant progression of a stress reaction.

There are many potential risk factors that can contribute to the formation of a stress fracture. While definitely not a complete list, here are two of the more important factors;

- Load management / recovery (Cosman et al., 2013)

- This refers to the relative amount of bone loading you normally complete compared to new demands. If appropriately paced and if appropriate recovery is allowed, increased training loads will allow adequate bony healing and adaptation

- This is particularly important if beginning a new or higher intensity activity which involves a higher bone workload

- Nutrition (Griel et al., 2007)

- The bone remodelling process requires a supply of energy for effective bone creation and turnover. If there is an energy availability deficit due to dietary factors, this can play a significant role in inadequate bony healing and potential bone stress formation.

Bone stress injuries can be complex to manage and often involve collaboration with many stakeholders, including orthopaedic specialists, sports physicians, physiotherapists, dieticians and more. If you would like to know more about bone stress and rehabilitation following an injury, please reach out to your CHP/R and INP physios!!

Billy Williams

Titled Sports and Exercise Physiotherapist

References:

- Cosman F, Ruffing J, Zion M, Uhorchak J, Ralston S, Tendy S, McGuigan FE, Lindsay R, Nieves J. Determinants of stress fracture risk in United States Military Academy cadets. Bone, 55(2), 359-66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.04.011.

- Griel AE, Kris-Etherton PM, Hilpert KF, Zhao G, West SG, Corwin RL. An increase in dietary n-3 fatty acids decreases a marker of bone resorption in humans. Nutrition Journal, 6:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-2.

- Frost HM. A new direction for osteoporosis research: a review and proposal. Bone, 12(6), 429-37. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(91)90032-e. PMID: 1797058.

- Posted In:

- General